![]()

Coasts

Rivers/Lakes

Lowlands/Plains

Geysers/Mud

Glaciers

Mt. Ruapehu

Mt. Cook

White Island

A Maori Legend

![]()

Abbotsford

Aramoana

Ballantynes

Brynderwyns

Cave Creek

Hawkes Bay

H.M.S. Orpheus

Influenza

Mt. Erebus

Mt. Tarawera

Rainbow Warrior

Seacliff Hospital

Tangiwai

Wahine

![]()

Annie Aves

Ata-hoe

Daisy Basham

Jean Batten

Minnie Dean

Mabel Howard

Margaret Mahy

Kath Mansfield

Kate Sheppard

Kiri Te Kanawa

Catherine Tizard

Murray Ball

Charles Goldie

Edmund Hillary

Richard Pearse

Lord Rutherford

Charles Upham

![]()

NZ FAQ--Funny

NZ Links

Credits

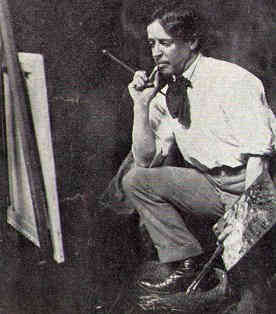

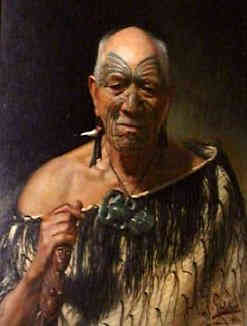

"Owing to the influence during the last fifty or sixty years of impressionism, futurism, cubism and many other isms, I venture to say that very few artists living today have the knowledge necessary to paint an important subject-picture with success as did the masters of forty years ago. Present-day art generally speaking is, in my opinion, on a much lower plane than that of the "Primitives" or even before that. It seems to me that the time is not far distant when it will be necessary for visitors to be conducted through art galleries by interpreters." -C.F. Goldie. Charles Frederick Goldie (1870-1947) is one of New Zealand's most controversial and best-known painters. He has been variously described as 'our greatest painter', an 'outdated, academic racist', and no more than a 'second-rate Lindauer'. Many critics considered his paintings of Maori factual recordings rather than art. They placed them on an equivalent level with the hand-coloured photography being undertaken at the same time. Critics comments ran the gamut from, "valuable documentation, but not art. A picture by Goldie imparts information and it is only on that level that his work will survive", to, "more suitable for a museum of ethnology and anthropology than for the walls of an art gallery", to, the rather more complimentary, "his paintings lose none of their acute detail but rather gain when put under a magnifying glass". Detail was where Goldie was at his most powerful. He could paint wrinkles, skin, hair and feathers with amazing realism. The suggestion has been made that he may not have liked painting eyes as his subjects were often positioned looking to one side or with their eyes in shadow.

Back when Goldie was painting many people believed the Maori to be a doomed race. At that stage there remained very few men that still had the old chiselled ta moko or facial tattooing. This had ceased in the 1860s. Tattooing was widespread throughout Polynesia, but nowhere else were there designs similar to those found among the Maori. These intricate details denoted the wearer's status and their exploits. They were carved using albatross bone, shark's tooth or seashell chisels and a dark pigment inserted simultaneously. Goldie's presentation of his Maori art portraits with almost photographic attention to detail conveyed an impression of naturalism, but were also posed and artificial. His paintings rarely show young, vital Maori adapting to and embracing the future, but instead concentrate on elders often appearing worn-out, submissive and defeated. This was accentuated by the titles of Goldie's works. Titles such as Tumai Tawhiti: The Last of the Cannibals, Patara Te Tuhi: an Old Warrior and The Last Sleep add to the impression that these Maori are the last survivors of a dying race. Right into the 1940s Goldie continued to portray elderly Maori in traditional costume and settings. In his work he failed to show the many challenges to their traditional lifestyle which Maori had encountered and overcome. As time passed Goldie was increasingly dismissed by art critics, who considered he had a very limited subject range. Requests for him to vary his topics fell on deaf ears. Goldie continued to exhibit new works every year until 1919, though many were replicas of earlier paintings and some depicted sitters who had long since died. In 1930, encouraged by the Governor-General, Goldie sent work to London to be exhibited with the Royal Academy and at the Paris Salon. Overseas critics did not share the feelings of their New Zealand counterparts, Goldie's work was greatly admired, and he received King George V's Silver Jubilee Medal and an OBE in 1935. The Goldie painting most resented by Maori is 'The Arrival of the Maoris in New Zealand (1898)'. Painted in collaboration with Louis Steele the work depicts the arrival in New Zealand of the 'Great Fleet'. Objections come from the way Maori are shown as desperately starving and thirsty while elated at the final sighting of land. The work shows Maori as ship wreck survivors rather than the master navigators they really were. While there are many critics of this painting, it is still reproduced more than any other work by Goldie. From 1940

onwards Goldie was in failing health and he died at the age of seventy-six.

At his death the Auckland City Art Gallery had an extensive collection

of Goldie's works on loan from the artist. The fifty-eight pictures,

twenty-nine Maori studies and twenty-nine copies of Old Masters,

had been there for twenty-seven years. Upon his death Goldie's widow

requested the return of the paintings and since that time some have

found their way into art salerooms. The irony is these paintings

had been offered to the Auckland City Council for the low sum of

NZ$8,000 at a time when Goldie would have been glad of the money.

|