![]()

Coasts

Rivers/Lakes

Lowlands/Plains

Geysers/Mud

Glaciers

Mt. Ruapehu

Mt. Cook

White Island

A Maori Legend

![]()

Abbotsford

Aramoana

Ballantynes

Brynderwyns

Cave Creek

Hawkes Bay

H.M.S. Orpheus

Influenza

Mt. Erebus

Mt. Tarawera

Rainbow Warrior

Seacliff Hospital

Tangiwai

Wahine

![]()

Annie Aves

Ata-hoe

Daisy Basham

Jean Batten

Minnie Dean

Mabel Howard

Margaret Mahy

Kath Mansfield

Kate Sheppard

Kiri Te Kanawa

Catherine Tizard

Murray Ball

Charles Goldie

Edmund Hillary

Richard Pearse

Lord Rutherford

Charles Upham

![]()

NZ FAQ--Funny

NZ Links

Credits

April 10th, 1968. The Wahine,

(woman), was the second ship to bear the name, and at 9000 tons,

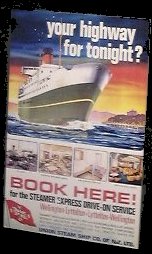

the biggest in the Union Steamship Company line. Referred to as

a 'steamer express' by the company publicity department, when completed

in 1966 she was also one of the largest ferries in the world.

Good Friday of 1968 bought tropical cyclone Giselle to New Zealand. Across the country it was to cause much havoc including tearing off roofs, bringing down powerlines and causing the sinking of the roll-on, roll-off passenger ferry, Wahine. On the ship that day were 610 passengers and a crew of 125 though the Wahine was easily capable of carrying over 980 passengers. None of the passengers or crew expected a difficult crossing, word was that the cyclone was still too far distant to be a problem, there was only a slight breeze, and the weather did not seem bad nor the sea rough. During the night the wind increased and seas became rough. By the time the Wahine approached Wellington Harbour the winds were gale force and waves were huge. At times she was lifted so high that her propellers were out of the water. As the Wahine came opposite Pencarrow Head at the harbour entrance the wind was gusting up to 160 kilometres and hour. Suddenly a freak wave hit the ship tearing her to port -- where lay the dangerous rocks of Barretts Reef. The captain fought to correct the drift but a second wave struck, throwing him 22 metres across the bridge -- all of it in the air. The ship was now horribly off course with radar down and nil visibility. Captain Robertson decided to take the Wahine back out of the harbour but it was too late and control of the vessel was unable to be regained. She continued to drift in the direction of the jagged Barretts Reef rocks, which also took the trans-Tasman passenger ship, Wanganella in 1947. This reef is normally given a wide berth by all shipping. Wahine grounded stern first onto Barretts Reef just after 6.40 a.m. Few passengers felt the grounding and most were oblivious to what was going on. Alarm bells were rung, the following announcement made: "Ladies and gentlemen, we are aground on Barretts Reef. There is no immediate danger. Please proceed to your cabins, collect you life jackets, and report to your muster stations."

The ship was lifted off the rocks by the huge waves then started to drift down the harbour. The crew responded by dropping her anchors. At this stage four underwater compartment were flooded but the pumps were working well at keeping the remaining compartments dry and there was no chance of a sinking. Later it was discovered that water had started to enter the vehicle deck. This was the biggest threat to the vessels stability but there was no way of removing it. Hopes were held that the ship might be able to be towed to safety into more shelter waters. For the next few hours the Wahine drifted slowly down the entrance of Wellington harbour. At 11.00 a.m. the tug Tapuhi was able to get a line to the ship but this broke after ten minutes and it proved impossible to reattach it. Deputy harbourmaster Captain Galloway then risked his life leaping from a pitching launch to clamber up a ladder dangling over the starboard side of the ship. He just missed being crushed when the launch came back and hit the Wahine. By 1.00 p.m. the wind had dropped a little although the seas remained very rough. The tide swung Wahine side-on to the wind providing some shelter on the starboard side. At the same time her list to starboard increased noticeably. At 1.15 p.m. passengers and crew were instructed to abandon the ship on the starboard side. During the day the captain and crew had intentionally misled the passengers into believing there was no danger. They felt this was preferable to telling everyone about the possible dangers and risking widespread panic. As a result, when the order was given to abandon ship passengers were stunned. Many felt they were safer onboard and some had even removed their life jackets to use them as pillows. Others did not know which side was starboard and instead made their way to the high side of the ship from which it was impossible to launch boats. The decks were very slippery and wet with a list so great that passengers slid across the decks to collide with walls and rails. The four lifeboats on the starboard side were launched. One was driven across the harbour and capsized before it could reach shore. The others land safely on the beach at Seatoun. Wahine was within sight of the shore and a large number of other vessels, including another ferry, the Aramoana, had gone to pick up those in rafts. Some passengers were left with no choice but to jump from the listing vessel straight into the cold water and, along with many of those in rafts, they were blown across the harbour towards Eastbourne Beach, an area with difficult access. Debris on the road caused by the storm meant that rescue vehicles couldn't get onto the beach itself.

As the canopied rubber rafts approached the shore waves as high as 6 m capsized them and many lives were lost at this time. Only eight police officers were initially able to get down to Eastbourne and they co-ordinated most of the early rescue activity followed by one hundred other officers and one hundred and fifty civilians. Dead bodies washed up along this stretch of beach and some people who made it onto the shore alive were unable to be given medical attention quick enough to prevent death from exposure. Others drowned or were dashed against the rocks by the pounding surf. As tradition demands the captains were the last to leave by diving over the side, now nearly level with the sea. Despite all rescue attempts 51 people lost their lives, 43 on the difficult to access eastern shore and 8 in the water. A court of inquiry was convened ten weeks later, and in December of that year was to return with a list of errors and omissions made both onshore and aboard the ferry. But, at the same time, it was noted that these occurred under very difficult and dangerous conditions. The inquiry found the primary reason for the Wahine's capsize was the presence of water on the vehicle deck. Fault was found with Captain Robertson for failing to report this to those onshore and also not reporting that the ship's draught had increased to 22 feet after striking the reef. An attempt was made to raise the Wahine in one piece but she broke up and was eventually salvaged in pieces. Her mast stands in Frank Kitts Park in Wellington as a memorial for those who died.

|